Have you noticed the quirky tigers and vibrant colors in trending shows like K-Pop Demon Hunters? Minhwa is a traditional Korean folk painting style from the late Joseon Dynasty characterized by its bold colors, humorous depictions of animals, and freedom from formal artistic rules. Unlike the solemn art of the court, Minhwa captures the raw energy, wit, and unfiltered dreams of the common people. In this article, I will guide you through the rebellious history of Minhwa, its surprising roots in ancient ceramics, and why it is currently the biggest muse for modern K-Illustration.

- The Spirit of Rebellion: What is Minhwa?

- Decoding the Canvas: Key Themes and Meanings

- The Aesthetic Ancestor: Buncheong Ware and Freedom

- Guardians of Folk Art: Scholarly Perspectives

- From Paper to Pixel: The K-Art Renaissance

The Spirit of Rebellion: What is Minhwa?

Living in Korea, I often see these paintings not in museums, but in hip cafes and souvenir shops. This accessibility is the very essence of Minhwa. While the elite Yangban class enjoyed “Munindo” (literati paintings) that emphasized restraint and Confucian philosophy, Minhwa was the “Pop Art” of the 17th to 19th centuries.

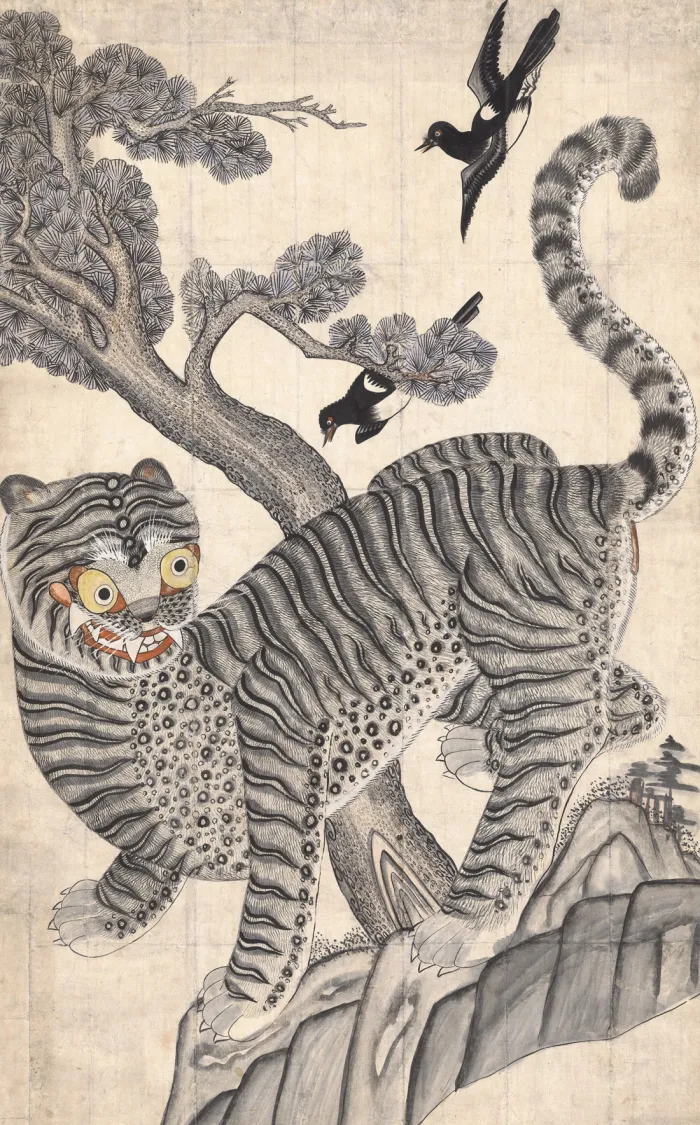

Created mostly by anonymous, wandering artists, these works were free from the strict obsession with perspective and realism that dominated court art. Instead, they focused on emotional truth. The subjects were often distorted or exaggerated—not because the artists lacked skill, but because they prioritized the storytelling and the magical wish for good fortune over technical perfection.

Decoding the Canvas: Key Themes and Meanings

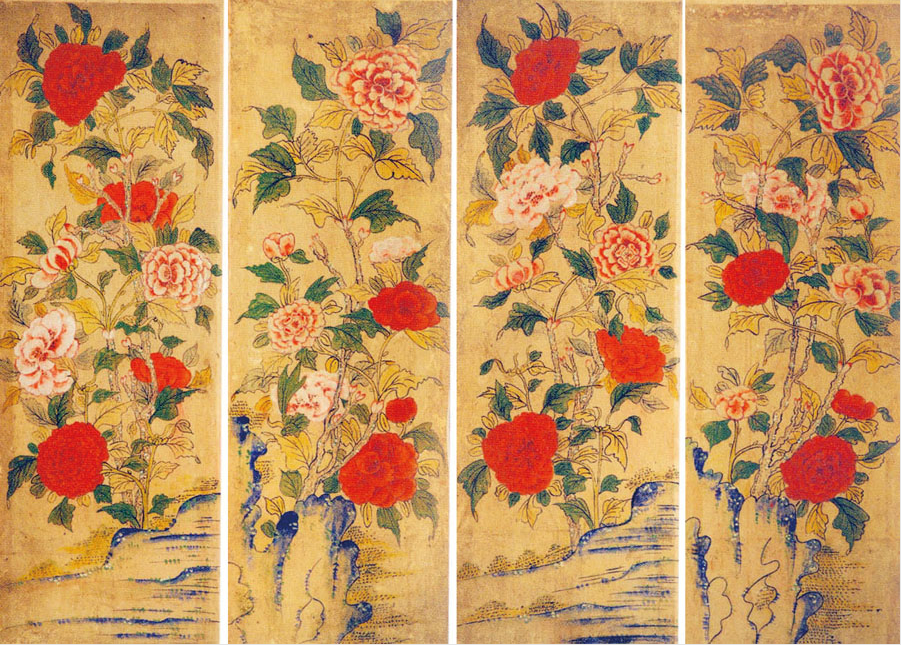

Minhwa is essentially a visual language of hope. Every element in the painting acts as a symbol for a specific wish, be it long life, many children, or protection from evil spirits. The use of the five cardinal colors (Obangsaek) is particularly striking, creating a visual vibrancy that feels incredibly modern.

For a deeper understanding of the philosophy behind these colors, I highly recommend reading our article on Obangsaek: Decoding Korea’s Cosmic Colors and Irworobongdo.

The Language of Symbols

| Subject | Korean Name | Hidden Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Tiger & Magpie | Hojakdo | Satire of corrupt officials (Tiger) and good news (Magpie) |

| Peonies | Morando | Wealth, honor, and royal dignity |

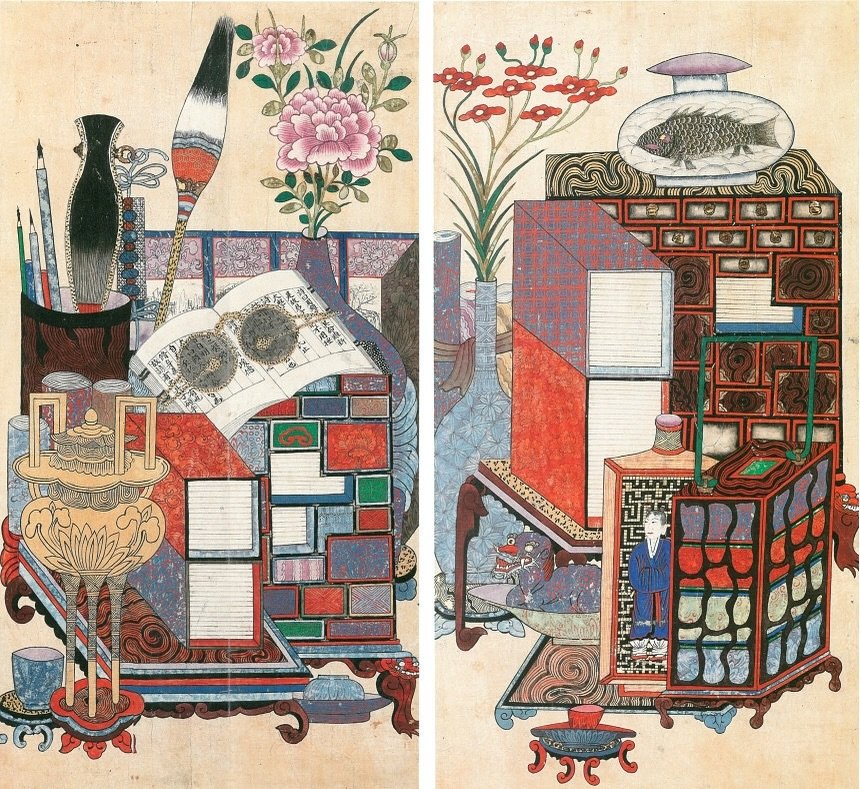

| Books & Shelves | Chaekgeori | Scholarship and social advancement |

| Lotus Flowers | Yeonhwado | Purity and creation (often linked to Buddhism) |

The Aesthetic Ancestor: Buncheong Ware and Freedom

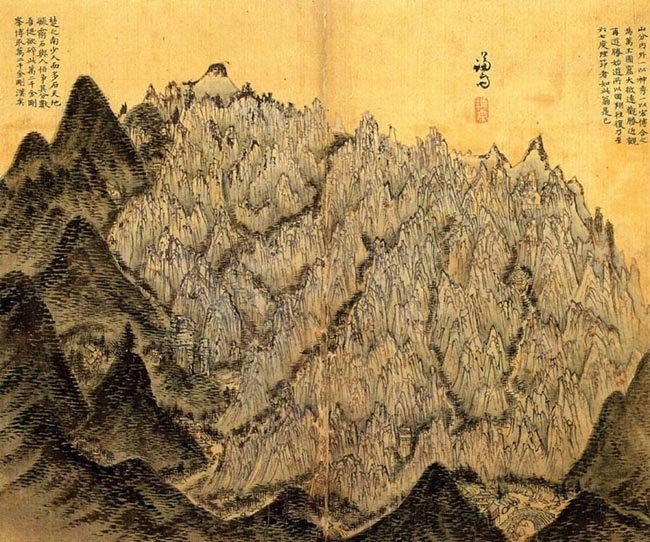

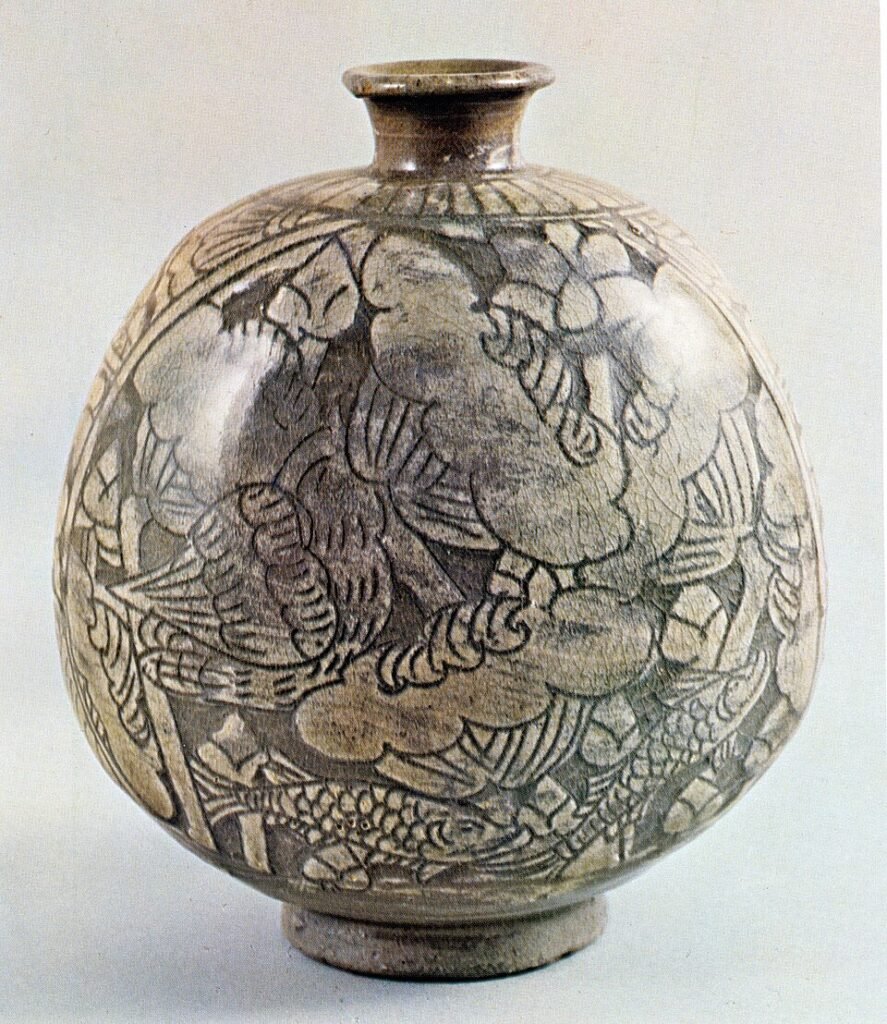

To truly grasp the “freestyle” nature of Minhwa, we must look back to the early Joseon Dynasty (15th–16th century) and the emergence of Buncheong Ware. Before Minhwa became popular on paper, the spirit of abstraction was already alive in ceramics.

Buncheong pottery is famous for its grayish-blue clay covered in white slip. What makes it the spiritual ancestor of Minhwa is the decoration technique. Potters used rapid, coarse brushstrokes (a technique called Gwi-yal) to draw fish, flowers, or abstract lines. These drawings were often asymmetrical, childlike, and wonderfully imperfect.

I view Buncheong as the “sketchbook” of the Korean soul. The carefree energy found in a clumsily drawn fish on a Buncheong flask is the exact same DNA found in the grinning tigers of later Minhwa paintings. Both reject the rigid perfection of their predecessors (Goryeo Celadon and Court Painting, respectively) in favor of a humanistic, natural aesthetic.

Guardians of Folk Art: Scholarly Perspectives

For a long time, Minhwa was dismissed as “vulgar” by traditional critics. However, visionary scholars have re-evaluated its importance. The most notable figure is Zo Zayong (Cho Ja-yong), the founder of the Emille Museum. He was a tireless advocate who argued that the “Tiger” in Minhwa represents the resilient and humorous spirit of the Korean people. He championed the idea that Minhwa is not just bad imitation of high art, but a unique genre of “creative resistance.”

Another key perspective comes from art historian Kang Woo-bang. He analyzed the structural patterns in Korean art—from Goguryeo tombs to Buncheong and Minhwa—and identified a “dynamic energy” (Gi) that flows through them. Scholarly consensus today agrees that the distortion found in Minhwa is a deliberate artistic choice, reflecting a sophisticated “Modernism” that predates Western art history.

📌 Insight: The “silly tiger” isn’t just cute. It’s a satirical caricature. By painting the feared beast as a foolish creature, commoners were subtly mocking the oppressive power of the aristocracy.

From Paper to Pixel: The K-Art Renaissance

Fast forward to the 21st century, and Minhwa is experiencing a massive revival in the digital age. The bold outlines and flat color fields of traditional folk art translate perfectly to digital illustration, making them a favorite subject for tablet artists and graphic designers.

The “Minhwa Tiger” has become a streetwear icon, and the “Chaekgeori” (bookshelf) pattern is being reimagined as modern wallpapers. This phenomenon proves that the desire for auspicious symbols and humorous storytelling is timeless. If you want to explore the full timeline of how Korean painting evolved to this point, do not miss our Guide to Traditional Korean Painting History.

Modern K-Illustration is not just copying the past; it is evolving the spirit of Minhwa—using art to express the joys, sorrows, and wit of everyday life in contemporary Korea.

Korean Culture portal KCulture.com

Founder of Kculture.com and MA in Political Science. He shares deep academic and local insights to provide an authentic perspective on Korean history and society.

🇰🇷 Essential Seoul Travel Kit

- ✈️ Flights: Find Cheap Flights to Seoul

- 🏨 Stay: Top Rated Hotels in Seoul

- 🎟️ Tours: Best Activities & K-Pop Tours