If you have ever stepped inside the National Museum of Korea in Seoul, you may have felt a sense of quiet awe standing before a massive ink-wash scroll. At first glance, the history of traditional Korean painting can feel like a mystery of black ink and vast white spaces. However, as someone living in Korea who has spent countless weekends lost in these galleries, I can tell you that these aren’t just old pictures—they are the soul of a nation captured on silk and paper. If you are seeking the ‘real’ Korea, you must experience its culture through its visual legacy, from the fierce murals of ancient tombs to the humble, humorous sketches of 18th-century village life. Understanding the evolution of these works will transform your next museum visit from a simple walk-through into a deep, emotional journey through time. If you’re planning a visit to the National Museum of Korea, I highly recommend reading this short guide before you go.

- Ancient Foundations: Spirits on the Walls

- Goryeo Dynasty: The Golden Age of Buddhist Splendor

- Early and Mid-Joseon: Establishing the Scholar’s Brush

- Classifying Joseon Art: Royal, Literati, Genre, and Folk

- Jeong Seon: The Man Who Painted the Real Korea

- Kim Hong-do and the Masters of Humanism

- Kim Jeong-hui: The Stark Beauty of Integrity

- The Missing Masterpieces: Why Our Art is Scattered Abroad

- The Living Legacy: How to Experience Korean Art Today

Ancient Foundations: Spirits on the Walls

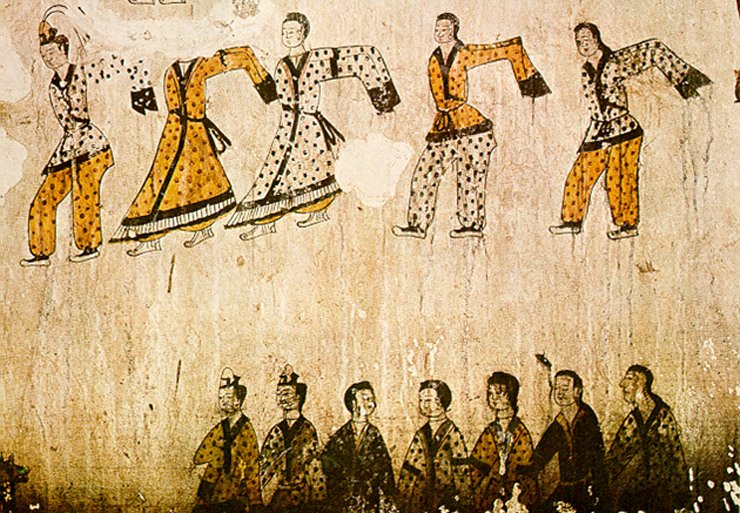

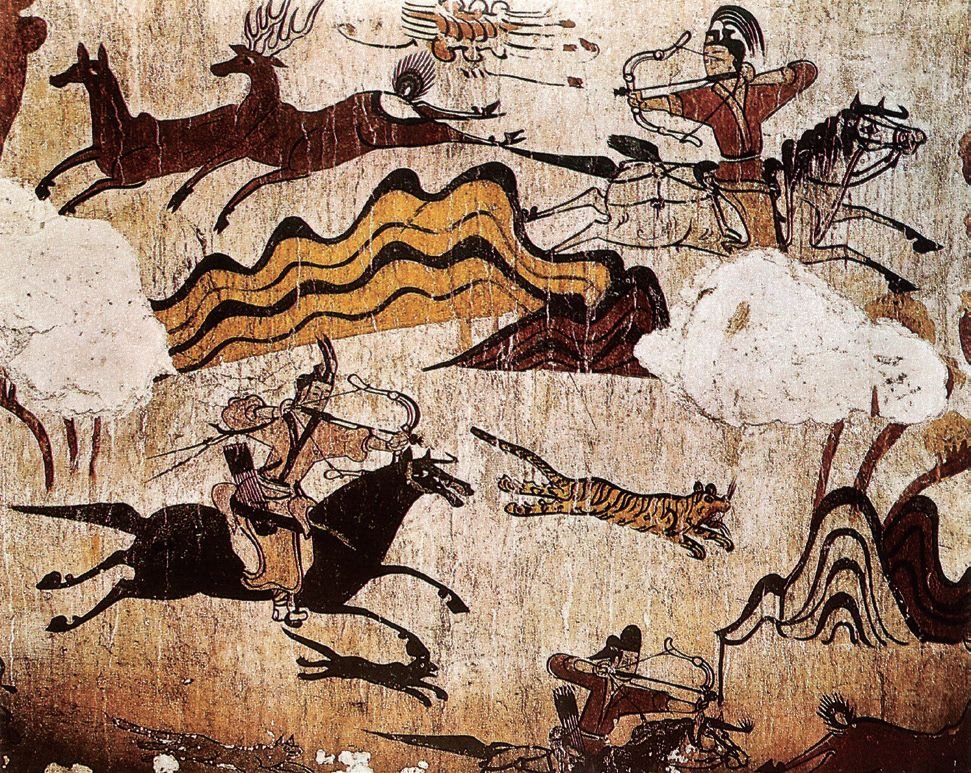

The story of Korean painting doesn’t start on a scroll; it starts on stone. If you want to understand the “DNA” of Korean aesthetics, you have to look at the Three Kingdoms period (Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla). Living in Korea, I’ve always been fascinated by how these early artists balanced raw power with delicate grace.

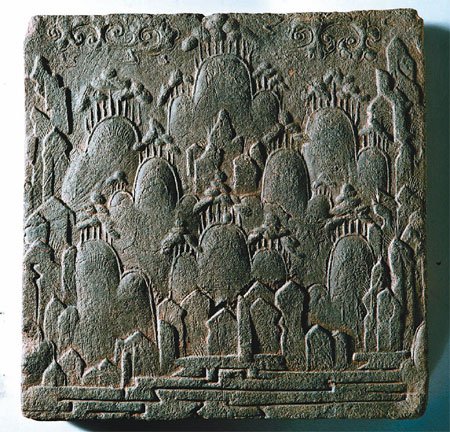

Goguryeo (37 BC – 668 AD) was known for its warrior spirit, reflected in tomb murals. In works like the Muyongdo (Dancing Scene) found in the Muyongchong Tomb, the lines are rhythmic and full of energy. The famous Sasindo (Four Guardian Deities) shows a level of mythical imagination that still feels modern today. Baekje offered a more refined, elegant touch, seen in their Sansumun-jeon (Landscape Patterned Tile), which shows a peaceful, balanced view of nature. Silla brought a heavy focus on Buddhist themes as the religion took deep root in the peninsula.

Goryeo Dynasty: The Golden Age of Buddhist Splendor

If you love intricate details and gold, the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) is your era. This was the peak of Buddhist influence in Korea. Goryeo Buddhist paintings, or Goryeo Bulhwa, are world-renowned for their sophistication. Unlike the later, simpler ink paintings, these were vibrant, using expensive pigments and “gold mud” (gold powder mixed with glue).

The masterpiece of this era is the Suwol Gwaneumdo (Water-Moon Avalokitesvara). What makes Goryeo art so special is the “reverse painting” technique—applying colors to the back of the silk to create a soft, glowing effect. When you see a high-quality Goryeo Buddhist painting, the transparent veil of the Bodhisattva looks so real it’s hard to believe it was painted over 700 years ago.

Early and Mid-Joseon: Establishing the Scholar’s Brush

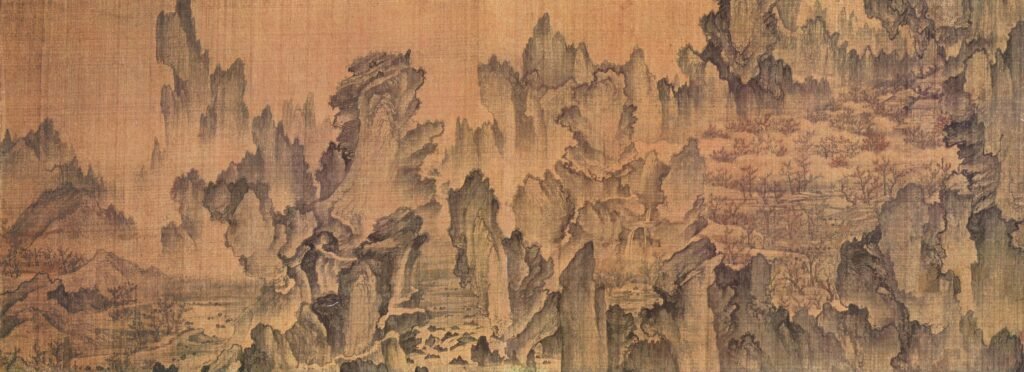

As we transition into the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), the vibrant colors of Goryeo faded, replaced by the restraint of Neo-Confucianism. During the Early Joseon (15th–16th Century), artists like An Gyeon emerged. His Mongyu Dowondo (Dream Journey to the Peach Blossom Land) used Chinese Northern Song techniques but organized space in a uniquely Korean, dreamlike fashion. Another notable figure was Kang Hui-an, whose Gosa Gwansudo (Scholar Contemplating Water) perfectly embodies the early scholar-painter’s meditative spirit.

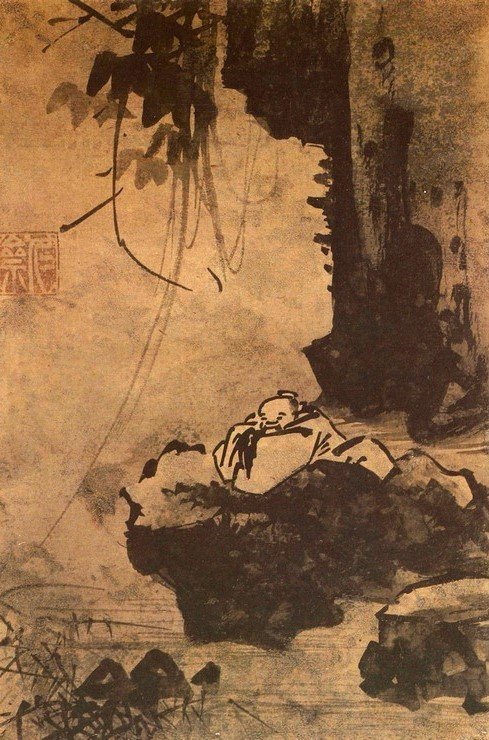

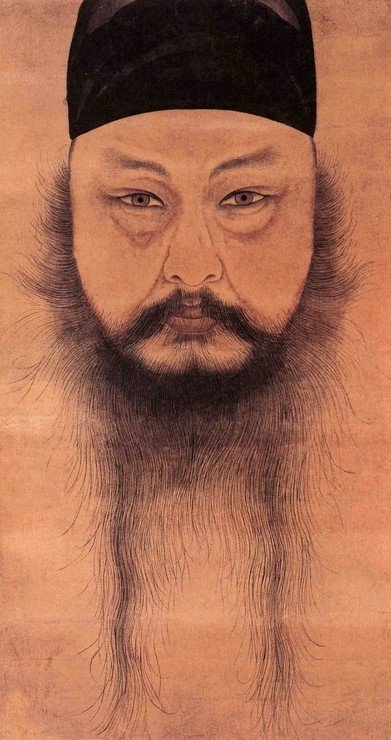

The Mid-Joseon (17th Century) was a period of transition and individual expression. Kim Myeong-guk became famous for his wild, unrestrained brushwork, best seen in his Dalmado (Painting of Bodhidharma). This period also saw the rise of Yun Du-seo, a scholar-painter whose “Self-Portrait” is so detailed and psychologically intense that it feels as if he is staring directly into your soul from the 1700s.

Classifying Joseon Art: Royal, Literati, Genre, and Folk

To truly understand Korean painting, you need to recognize the “Big Four” categories that defined the Joseon era. They weren’t just styles; they represented the social hierarchy and values of the time.

| Category | Main Characteristics | Key Examples/Artists |

|---|---|---|

| Royal Court Art | Formal, colorful, authoritative. Used for royal authority and ceremonies. | Irworobongdo (Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks) |

| Muninhwa (Literati) | Ink-wash, focused on the scholar’s inner spirit and integrity. Avoided technical “show-off.” | Four Gentlemen, Kim Jeong-hui (Chusa) |

| Pungsokhwa (Genre) | Realistic depictions of everyday life—from noble leisure to common labor. | Kim Hong-do, Shin Yun-bok |

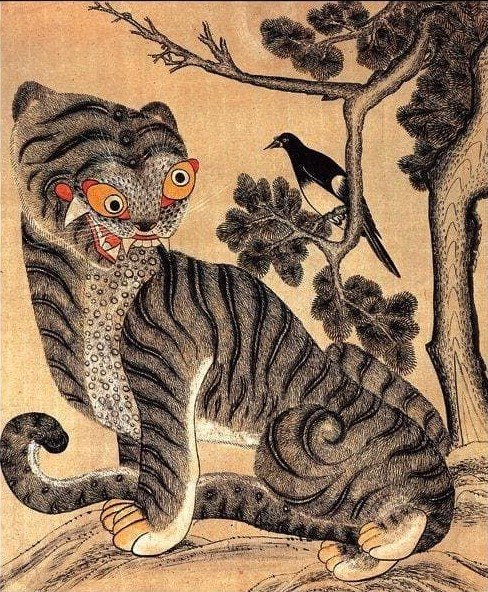

| Minhwa (Folk Art) | Anonymous, colorful, and symbolic. Painted by commoners to bring luck and ward off evil. They flourished during the late Joseon Dynasty. | Tiger and Magpie paintings, Peonies |

The biggest distinction to remember is between Pungsokhwa and Minhwa. While Pungsokhwa (Genre) was often painted by professional masters like Kim Hong-do to capture the reality of life with high skill, Minhwa (Folk) was the art of the people. Minhwa was often bold, flat, and humorous, using symbols like the tiger (the protector) and the magpie (the messenger of good news) to decorate common homes. To learn more about minhwa, refer to ‘Minhwa: The Guide to Korea’s “Pop Art” Tradition‘.

Jeong Seon: The Man Who Painted the Real Korea

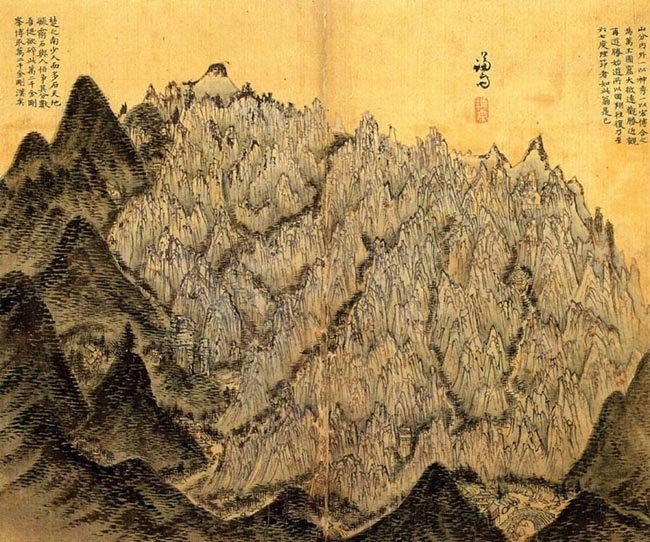

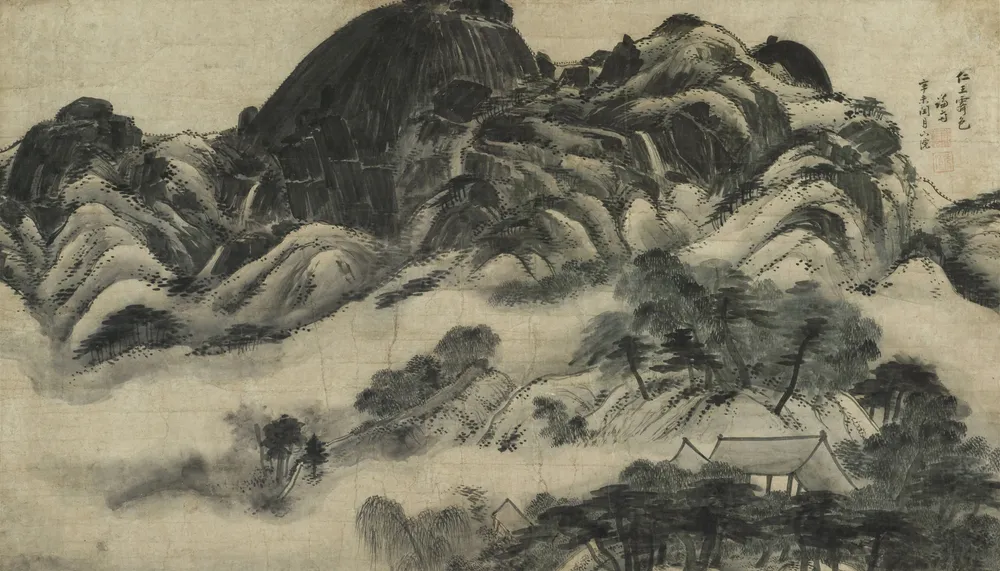

In the late Joseon period, Jeong Seon (pen name Gyeomjae) changed everything. He pioneered Jingyeong Sansu, or “True-View Landscape Painting.” Before him, painters copied imaginary Chinese mountains. Jeong Seon hiked the actual mountains of Korea—the Geumgangsan and Inwangsan—and painted what he saw.

His masterpiece, Inwangjesaekdo (Clearing After Rain on Mt. Inwang), used bold, heavy, “wet” brushstrokes to show the dampness of the granite rocks after a summer storm. He essentially gave Korea its own artistic identity, proving that the local landscape was a masterpiece in its own right.

Kim Hong-do and the Masters of Humanism

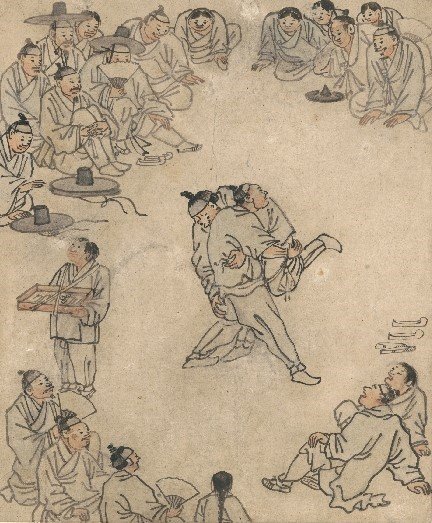

Kim Hong-do (Danwon) is arguably the most beloved painter in Korean history. While he was a genius at royal portraits, his true legacy lies in Pungsokhwa. His Ssireum (Korean Wrestling) captures the sweat, humor, and joy of a village festival. He wasn’t alone, though. His contemporary Shin Yun-bok (Hyewon) focused on the “leisure” side of Joseon—the romance and parties of the upper class—using delicate lines and vibrant colors.

Later in the 19th century, Jang Seung-eop (Owon) emerged as a wild genius who mastered almost every style, from landscapes to flowers and animals. These artists together shifted the focus from the heavens and the scholars’ ideals down to the lived experience of the Korean people.

Kim Jeong-hui: The Stark Beauty of Integrity

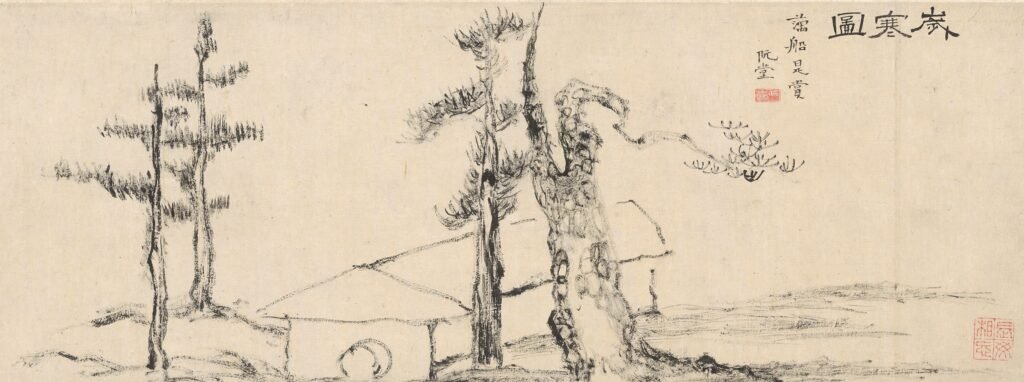

Kim Jeong-hui (Chusa) was a giant of calligraphy and scholarship. His most famous painting, Sehando (Winter Scene), is a raw, emotional thank-you letter to his student Yi Sang-jeok, who remained loyal during Chusa’s lonely exile on Jeju Island.

It is an “ink-dry” masterpiece—rough, simple, and stark. The pine and cypress trees in the painting symbolize the student’s unwavering integrity in the “winter” of Chusa’s life. It is the ultimate example of Muninhwa, where the story behind the brush is more powerful than the paint itself.

The Missing Masterpieces: Why Our Art is Scattered Abroad

It is a bittersweet reality that some of the greatest Korean paintings are currently located outside the peninsula. Because of Korea’s turbulent history, over 240,000 Korean cultural assets are estimated to be held abroad across 27 countries. Here is the scale of the distribution:

- Japan: Approximately 110,000 items (The largest portion, largely due to the Imjin War and the colonial period).

- USA: Approximately 65,000 items (Many acquired during the Korean War and through donations).

- Germany: Approximately 15,000 items (Collected by missionaries and diplomats).

These pieces, like An Gyeon’s Mongyu Dowondo currently in Japan, are not just “art”; they are fragments of our history waiting to be reunited with their home. Fortunately, the Lee Kun-hee Collection donation in 2021 brought thousands of masterpieces back into the public hands at the National Museum of Korea, sparking a new era of cultural pride.

The Living Legacy: How to Experience Korean Art Today

Traditional Korean painting is a window into a culture that values harmony with nature, intellectual integrity, and a good sense of humor. When you visit a museum in Korea today, look for the Yeobaek (empty space). It isn’t “blank”—it is space for you to breathe and think. Whether it’s the fierce colors of Goryeo or the humble tigers of Minhwa, these works are the living breath of Korea’s past.

📌 Local Note: If you want to see these masters, the National Museum of Korea and the Kansong Art Museum are the two most important places to visit. Kansong, in particular, holds many of Jeong Seon’s and Shin Yun-bok’s most famous works.

Korean Culture portal KCulture.com

Join the mailing service and add to your favorites.

Founder of Kculture.com and MA in Political Science. He shares deep academic and local insights to provide an authentic perspective on Korean history and society.