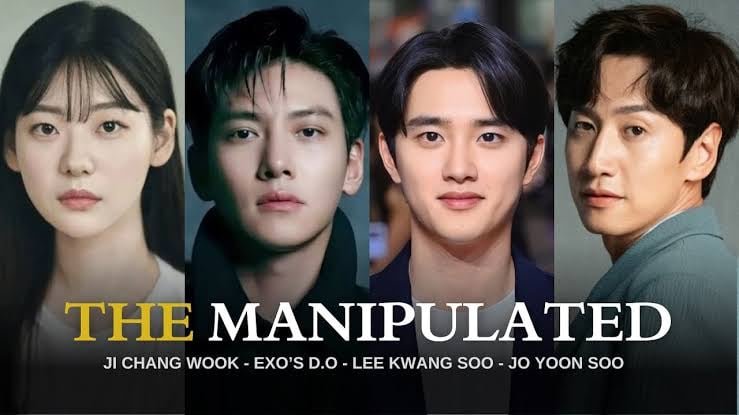

The blockbuster series starring Ji Chang-wook and Do Kyung-soo (D.O. of EXO) has officially dropped on Disney+, and it is already dominating social media conversations. While international viewers are streaming the show under the title The Manipulated, here in Korea, we know it by a slightly different, perhaps more chilling name: Jogak City (Sculptured City).

As a local people watching the series unfold, I can see that the show is more than just a revenge thriller; it is a sharp critique of modern digital society and social hierarchy. However, without understanding the specific Korean cultural context—from the hidden meaning of the original title to the unique portrayal of justice—you might miss half the story. Here is your “Deep Dive” cultural guide to fully appreciating The Manipulated.

- Title Analysis: “The Manipulated” vs. “Sculptured City”

- The “Designer”: Why Digital Hell is a Real Fear in Korea

- Vigilante Justice: A Symbol of Democratic Standards

- The Face of Innocence: Decoding D.O.’s Casting

- The Prison Hierarchy: Where Money Still Rules

Title Analysis: “The Manipulated” vs. “Sculptured City”

The English title, The Manipulated, perfectly describes the protagonist’s situation—he is a victim played by unseen hands. However, the original Korean title, Jogak City, shifts the focus to the villain and offers a much darker philosophical theme.

In Korean, “Jogak” means “Sculpture” or “Sculpting.” This word choice implies that the villain isn’t just tricking people; he is artistically and methodically carving their lives like a block of clay. The premise suggests that ordinary happiness can be chipped away until the individual is trapped in a “hell” designed specifically for them.

💡 Local Insight: The Korean title suggests that the city itself is a gallery for the villain, and the ruined lives within it are his “masterpieces.” While “manipulation” suggests control, “sculpting” suggests creation and total ownership. This nuance makes the villain’s malice feel far more god-like and terrifying to Korean audiences.

The “Designer”: Why Digital Hell is a Real Fear in Korea

The villain (played by Do Kyung-soo) is introduced as a “Designer” who fabricates realities to destroy lives. To some international viewers, the ease with which he dismantles the protagonist’s life might feel exaggerated or like science fiction.

The Context of Hyper-Connectivity

To understand the horror of this setup, you must understand the Korean digital environment. South Korea is one of the most connected nations on earth, which brings both convenience and vulnerability.

- Digital Identity: Our banking, government services, and social verification are deeply integrated into smartphones and phone numbers.

- Surveillance: Seoul is covered by a dense network of CCTVs and vehicle “black boxes” (dashcams).

In this context, the “Designer” represents a very realistic anxiety. If someone gains control of your digital footprint in Korea, they don’t just steal your money; they can edit your “reality.” They can frame you for crimes with deepfakes or destroy your social standing instantly. The show amplifies a fear that many Koreans share: our convenience can be weaponized against us.

Vigilante Justice: A Symbol of Democratic Standards

In the drama, Ji Chang-wook’s character chooses to walk into hell himself to seek revenge rather than relying on the law. A common question from Western viewers is, “Why don’t they just call the police? Is the system really that broken?”

It is important not to view this simply as “lawlessness.” Instead, this trope reflects the high standards Korean citizens hold for their society. Korea has a dynamic modern history where democracy was achieved through active citizen participation and protest.

The criticism of elites in our art is actually proof of a healthy, vigilant society that refuses to accept corruption or “absurdity” (Bujori). To help clear up this confusion, I’ve broken down how differently these scenes are interpreted by global vs. local audiences:

| Scenario | Western Perspective | Korean Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| The System | The country seems lawless or the police are villains. | Citizens hold the system to an impossibly high standard and refuse to accept incompetence. |

| The Vigilante | Why doesn’t he seek legal help? | Bureaucracy is too slow for the “Cider” (refreshing justice) that the public craves. |

| The Revenge | It looks like personal vendetta. | Revenge acts as a proxy for restoring social fairness against a rigged hierarchy. |

The protagonist’s struggle represents the individual’s fight for fairness. When he takes matters into his own hands, it delivers a catharsis (which we call “Cider”) that the slow-moving legal system cannot provide.

The Face of Innocence: Decoding D.O.’s Casting

Social media is abuzz with Do Kyung-soo’s chilling performance. For those who know him only as an actor, he may seem like a surprisingly young choice for such a heavy villain role. However, his casting is a deliberate cultural subversion.

The “Um-Chin-Ah” Twist: D.O. (from the group EXO) is famously known for his upright, polite, and “perfect son” image in Korea. By casting someone who represents the ideal, innocent youth as a psychopath who destroys lives, the drama delivers a shock to the audience.

It emphasizes a modern horror theme: Evil doesn’t look like a monster. It looks like a polite, successful young professional. This “face of an angel, mind of a devil” contrast makes his character far more unsettling than a traditional, scar-faced gangster.

The Prison Hierarchy: Where Money Still Rules

The prison scenes in The Manipulated offer another layer of social commentary. Unlike many Western prison dramas that focus on racial gangs or physical dominance, Korean narratives often focus on the extension of social class.

In the drama, the prison is depicted not as a place where everyone is equalized by punishment, but as a condensed version of the outside world.

- The “Chairman” Syndrome: It is a common trope (rooted in past real-life controversies) that wealthy criminals can buy comfort, authority, and even subservience from guards.

- Power Dynamics: The hierarchy is often determined by who has money and connections outside the walls.

The protagonist’s despair comes from the realization that even in prison, the “Designer’s” power can reach him. This reinforces the show’s critique of a materialistic society: if you have enough resources, you can “sculpt” your environment anywhere, even inside a cell.

Korean Culture portal KCulture.com

Join the mailing service and add to your favorites.

Founder of Kculture.com and MA in Political Science. He shares deep academic and local insights to provide an authentic perspective on Korean history and society.